The above 2-page newspaper article was published in the July 15, 1937 edition of the Indiana Journal. F. Allan Weatherbolt, Editor. Click HERE to see the entire original edition of that locally published newspaper, or read it below.

Like Present Vacationers, Forerunners of White Men Planned to Spend Part of Every Summer Enjoying Selves and Seeking Fish On Placid Lakes

The ancient Miami village of Ke-ki-on-ga was once the rendezvous for Indians of the Lakes. Here amongst a group of fifty wickiups lived one of the greatest Indians the world has ever known. He was Mi-shi-kin-noq-kwa, the Little Turtle. Small of stature, but brave and wise, he fought to save his country from the whites.

Acknowledged since the Revolution as the war chief of all Miamis, there came a time when he had no ordinary – border foray to deal with. By routing St. Clair’s men near Kekionga he temporarily blocked invasion of his hunting grounds until the coming of Mad Anthony Wayne in whose honor the village was renamed.

It was at the Battle of the Fallen Timbers that the glorious gate of the Wabash was closed to red men forever. They obeyed the summons to assemble at Fort Greenville where they signed a treaty establishing the Indiana boundary line. There followed several years of peace and Little Turtle retired to his village on Eel River, the Ke-na-po-co-mo-co.

Matchegan Begins His Training.

With him went many tribesman and Ba-da-fo-las, his famous medicine man, In the medicine lodge with Badafolas there had grown up an Indian youth named Mat-che-gan. He was chosen years before to learn the secrets of the old man’s mysterious knowledge of the spirit world and also his ability to imitate the wildlife of the forest. Rigid training had been his lot for upon him great responsibility would someday fall.

The Miamis were nomadic, wandering up and down the Mis-sis-sin-e-wa, the Wabash and the Eel on their seasonal hunting and fishing trips. The Pot-ta-wat-o-mies, whom General Harrison bade them call ‘brothers, chose the Tippecanoe and the rivers leading towards the north. All Indians liked the rivers because they were the natural highways for their canoes” hewed out of logs or made of bark. But they liked our lakes as well and planned to spend some time here every year.

On one of his hunting trips Papakeecha saw the graceful A-nou-gons, Little Star, neice of To-pin-a-be, tribal chief of “those who keep the fire”. Little Star went south with him, tearfully parting from her sister, Po-ka-gon’s wife, with whom she lived.

With Tecumtha On the Warpath.

When Te-cum-tha, defiant since the Greenville treaty, persuaded the Potawatomies that they should join the Shawnees to avenge their wrongs,

Papakeeche and Wawaesse disregarded the word of Little Turtle and joined the war party moving down the Tippecanoe, which they called Ke-tap-kwon for the buffalo fish abundant in the river. In Tecumtha’s absence, they let The Prophet’s promises to protect them with his many charms from the bullets of the whites lead them on to a disastrous defeat.

Going northward by the river route was Papakeecha, slightly wounded. With him was Win-a-mac, the Cat Fish, bent on vengeance and gathering warriors for the attack on Dearborn. Papakeecha refused to join him and by the Moon of Cracking Trees he reached Pokagon’s village where his squaw was waiting for him. With her was Whispering Winds, his son, called Ky-mo-tee by the Potawatomies and Ke-mo-te-ah by the Miamis. There was a little sister, Hen-zi-ga, the Brown Fair, whom Papakeecha had not seen.

Meanwhile Wawaesse journey to the old Miami town of Logansport, then makes his way northeast to Little Turtle’s village. Here he sought the latter’s pardon for following Tecumtha and his brother. He promised to be present at the council on the Mississinewa the following Moon of Flowers; he promised to gather scattered tribesmen and with Papakeecha to clear some land and found a village, Min- e o-ta-ni, on the northern lakes. Wawaesse thought well of this suggestion; he was tired of roving.

Meanwhile, Matchegan grew restless and unhappy. Little Turtle was adopting white men’s ideas which left old Badefolas much at sea. The thing that puzzled him the most was the new plan for vaccination. This the Indians did not understand. To them it seemed somehow to spell the doom of medicine men. Furthermore, Matchegan had spent his years of training, and gained much knowledge that he needed. He desired a medicine lodge all his very own.

He longed intensely for his friends of earlier Kekionga days. Among them were two young warriors, ’ Pa-pa-kee-cha, meaning Flat Belly, that is the “bedbug”, and Wa-wa-es-se, meaning Full Moon, the “round one”, sons of Ma-kin-gwa-mi-na, the Blackberry Flower, an aunt of Little Turtle. They now were powerful roaming chiefs, who came often to the village on their way to and from the lakes. Matchegan longed to join them and how he did happened in this way.

Miamis though they were, Papakeecha and Wawaesse found their squaws among the Pottawatomies. The latter wooed the sister of the powerful Metea when both lived near old Kekionga.

A Shaman Comes To Mayotika.

To Matchegan he turned for help; they would need a medicine man. Such a one as Machegan would give them much prestige and good advice. So it was that Matchegan left forever the lodge of Badafolas. With his parttieche and his symbols, he went with Wawaesse on to Metea’s minotani for the squaw and little daughter, Pa-ka-ta-ki, meaning “she blooms”. They had stayed in Mus-kwah-wah-se-pe-o-tan during years of border warfare.

Springtime found the brothers and their families encamped at the southern end of a long and beautiful lake, the largest in their hunting grounds. They called it Ma-yoti-ka, meaning’ Turkey Gobbler. They planned to build their minotani on the very highest ridge. Around its shores were many of their tribesmen gathered here together for the first time in many, many moons. And together went the brothers southward to the council called by Little Turtle where they saw him for the last time and promised him to keep from war.

Following happy years for the chieftains and their tribesmen on the shores of Mayotika. Next to them ranked Matchegan who interpreted the wishes of their Gods through visions, dreams, and omens. His duties there were manifold; he conducted ceremonial rites and feasts and dances; he had charge of preparations for the war and hunting parties; he brought forth the calumet; he invoked the rain and ministered to sick red men of the minotani. In short, he was their councilor, priest and healer.

Chief among his pleasures was his duty, self-imposed, of keeping watchful eyes upon Pakataki and Kymotee when their fathers were on the hunt or on their way to sign a treaty. Many things he taught these children; to them he was. the “one who knows all”. They liked to see him in his ceremonial dress; they were curious about his medicine bag, an otter skin pouch filled with herbs and charms and blowing tubes. On it was painted a centipede, the totem spirit of Matchegan.

The Children Learn His Secrets.

Sa-con-quan-e-wa, or Tired Legs, great uncle of the children, had come to live with them. Matchegan visited his lodge many times a week, for his joints were stiff and sore. He could not eat squirrel or rabbit meat else he, like those animals, might stay in a hunchback position forever. Every spring the Indian children followed Matchegan to gather tender fern fronds for his medicine. Matchegan explained that in the springtime these are coiled but unroll as the fern plant grows. An extract made from them should give the patient power to straighten out the drawn muscles of his limbs. Matchegan said that plants of pungent odor were best for healing because the smell puts to rout the demon of disease. To keep away malaria he smoked killikmic, the leaves, and bark of dogwood; for an emetic, he used blood wort or the golden seal, boneset tea for colds, ginseng for the ear ache, mandrake roots had various uses. They helped him gather black cohosh, skunk cabbage and sassafras at the proper time of year. When an herb was gathered they learned to read the prescription stick and chant with him a gentle song of thanks.

An earth mound he used for vapor baths; wounds were closed with small bone needles threaded with strong sinew. Bits of wood from trees with lightning were used in binding fractures. Bear grease, white pine wax and squash kernels were sometimes used in dressings. A hemorrhage he claimed he stopped with plaster made of buzzard’s down. Then there were gourd rattles hung about the lodge and bright bits of cloth he accepted as his fees. These fascinated the children.

Many other superstitions had the Indians. If the night owl hooted or if the family dog howled all the night, some one in the family would fall ill. If in the Moon of Wild Geese, a skunk was hung upon a pole outside the wickiup, then disease would be warded off until the Crow Moon, our month of April. Manchegan warned the children to spit when they saw a shooting star. This would prevent the toothache. Sometimes Kymotee thought he rather would be a shaman than to succeed his father as chief of all the beaver clan. Living on the edge of the tamarack swamp was Nash-a-bo-n.a, the old witch-squaw, from whom they learned one Pottawatomie legend of creation. When Kitch-e-mon-e-do made the world, he filled it with a class of beings who looked like men but really were ungrateful dogs who never thanked their creator. For this the Great Spirit plunged them and their world into a great lake and drowned them. He withdrew the world and up on it put a handsome young brave who soon became quite lonesome. Kitchemonedo took pity upon the warrior and sent to him a sister.

Legend Of Creation.

Awakening from a dream several moons thereafter, he told his sister what had been revealed to him. five youths would come to court her. in truth Wa-pa-ko, Esh-kos-si-min and U-sam-o came in turn and each she sent away. But when the fifth one, Mon-ta-min, which means maize, approached her, she threw back the tapestry door of her lodge and bade him enter. Her brother s dream thus guided the maiden in her choice.

Montamin forthwith buried the unsuccessful suitors in order of their appearance and from their graves grew pumpkins, melons, beans, and the tobacco, in this manner the Great Spirit provide food for his children and to this day they have smoked tobacco in their pipes of peace.’ From the union of Montamin and the maiden sprang the Indian race.

The sap crept up the trunks of Sa-na-min-gi; n came time to make the maple sugar when the wild geese honked their way back from southern feeding grounds. Pakalaki then put away her buckskin dolls and helped her mother. The fires were started and stones were heated. The children brought the yokes and buckets which old Si-nas-ta, the Expert, had made for them. At first the sap came slowly, then it dripped much faster.

Soon the boys and girls were filling hollowed logs with the sweet water. Squaws dropped in hot stones to make it boil. In three more days Palaki let bits of syrup drop from the paddle onto the snow. It was thick enough to harden. They ate and ate, then stored away the cakes for winter moons. Some sugar they poured on mussel shells and some they stuffed in colored bills of ducks and geese which they had saved; these they put away to celebrate the Indian’s New Year which came in March, Ma-kon-sa.

Other duties Pakataki had. She helped Ka-ma-ma, her father’s mother, weave the rush mats and the baskets for their wickiup. Before Wa-wa-sam-wa, the fireflies, disappeared, they gathered nettle fibers, rushes, reeds and grasses. For decorations they dyed some quills; yellow root made yellow, walnut hulls made brown, blood root or puccoon made shades of orange and red, berries made a bluish gray and butternut hulls made black. Kamama taught her how to tie the knots for fish nets weaving her brown fingers became faster than the spiders’ legs.

Both children loved the water. How they liked to paddle back across marshes of the tiny nestled among the hills play upon the wooded islands thereabouts! Many times a beaver pond or otter slide ‘and when I heard the bittern, lk-ka-w?? they thought the Thunder Bird had come to earth! It was such fun to find turtle eggs hidden in the sand! Roots of rushes and the yellow spatter ???? tasted like potatoes so they took them to Kamama. Pleased, she gave them balls of pemmican made of powdered acorns, wild cherries and dried fish.

Kymotee dressed like Papakeecha. In the summer he wore a breech cloth of soft buckskin trimmed with sh??? and beads and quills, and used moccasins only when he really needed them. Hair was caught in brush and brambles so he shaved his head with a sharp flint knife, braided the scalp lock left on top. Wild turkey feathers dyied tails of coons and claws of animals were used for ornaments at all feasts. In the winter there were shirts and leggings made of buffalo skins beaded with the family totem. To him his father gave a tomahawk and called it Ta-ta-wa-ki-ni.

Kymotee’s own totem was the muskrat, Sa-kwa.-It came to him after his fasting period followed by a dream. Os their skins his mother made a robe. He watched the muskrats slowly build their houses in the marshes. Sinasta showed him how to make the traps and Matchegan went with him to cut the willow stakes. Finally came the time when nights were warm and foggy; a period always following the first visit of Blue Spirits of the North; Kymotee knew when the rats would run. He knew, too, that left in traps too long they would gnaw as soon as daylight came. Before the dawn he set forth north towards the largest marshes.

Kymotee Saves The Minotani.

Dry, brown rushes and the cattails filled the half-moon-shaped bay. The edge he skirted, gathering rats into the boat and resetting all the traps. Drawing near the island to the west, he pushed his canoe back through the rushes until he reached an open pond. A filmy veil of mist was hanging oyer the water; light was breaking in the east. Kymotee made fast his canoe and prepared, to wade the marsh. Zip! Thug! He hopped from one clump of tangleroot to another to keep from sinking in the muck.

Then a creeping sensation went up along his spine. Curious, disregarding danger, he inched his way along a few feet farther until he came within earshot of some Indians. Friends,he sensed they were not; if they had been would they not have sent smoke signals to the minotani when they encamped the night before? From the high ground beyond big Mayouka, even the most disstant island to the northwest could be seen.

He could hear strange red men speaking on beyond him as the raiding party gathered for their breakfast of papaws and. smoked meat. Peeping through the wild rice Kymotee saw their painted laces and their gestures; he guessed they were the horse theives who took old Mus-qua-buck’s ten ponies one night the week before. In fact, they had the white one with them; he had ridden it when he and Matchegan had gone beyond Oswego to dig pink mallow roots in the Moon of the Falling Leaves.

Soon his father would be leaving on the hunt and Kymotee knew he must get back before they left to warn them. He could not paddle back across the water for discovery might mean instant death. The marsh was teeming with wildlife; the ducks were quacking as they dove and fought over bits of roots and moss. Every movement, quick and quiet, counted as he made his way back to the marsh’s edge. Abandoning his canoe and hidden by the rushes, he swam the icy water, underneath at times, until he reached the eastern point of land, going well around behind it before he left the water.

Keeping close,to shore behind the fringe of trees, he scrambled through the bushes back towards home. Rounding . the bay until he reached another island, then across the center until he reached the cranberry bog, again he took the water. Straight southwest he swam, the shortest way to reach his father. Machegan was aglow with satisfaction when he learned Kymotee’s valor; had he not rubbed the lad with eel oil to make him lithe and supple and had not his totem served him well? Papakeecha strengthened the guard around the minotani; the thieves, for lack of food, gave up their plans for raiding after waiting near for days.

When Blue Spirits came to stay, when they breathed cold blasts upon the water and changed it -into ice, then Kymotee had to help his mother find some food. Matchegan taught him how to make bone fish hooks; how to chop the right size hole; where the perch most often could be found. Sometimes they built a wigwam on the ice; then they could have a fire and Pakaiaki joined them. Joined them too on warmer days when they played the game of snow snake, Pi-sho-kwan.

They made a groove along the snow until the ice gleamed through. Kymotees snake was made of hickory and the head was painted gaily; totems trimmed the eight foot handle.

Often were their fathers absent from the camp, summons to meet with other tribes to sign a treaty came sometimes twice a year. The there was the annual pilgrimage to Little Turtle’s grave at Kekiongo. Papakeecha and Wawaesse often went away together, sometimes alone, to distant places. Many gilts were given them on these occasions; sometimes they signed with Chippewas, sometimes with the Pottawatomies but more often with Miamis. Each time more of their hunting grounds they gave away to eager whites. Each time they returned From these pow wows more embittered and dissatisfied.

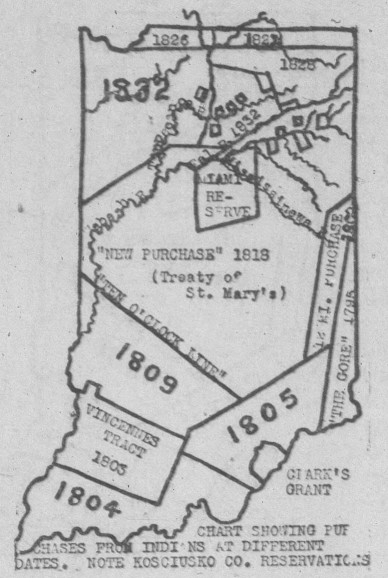

The Chiefs Sign Many Treaties.

Finally came a day in 1826 when Pokagon and the cousins of the bear totem stopped with them on their journey southward to the mouth of the Mississinewa on the Wabash where another treaty need be signed. Of Pokagon, Kymotee had heard much from his mother. Memories of her childhood lingered even though she had not seen her sister for many moons. Of Pokagon’s wagon she often told him—the first wheels to sink a furrow in the old Sauk trail. Crude though it was and drawn by ox and horse, it never ceased to be the envy of the tribesmen.

Four neighbor Potawatpmie chiefs went with them, Musquabuck, “Red sky at morning”, Che-cose, Mota and Me-no-quet. They joined Pokagon on his way to sign the treaty. Miami brothers followed ten days later. Here they had another promise of land set aside for them forever, “forever” meaning about ten years in white man’s language. A government agent, o-si-ma, gave them papers which they could not read. Papakeecha would have a reservation; a brick house would be built upon it; a mill to grind their corn, a blacksmith, cattle, salt, horses and tobacco would be provided. Papakeecha came home in highest spirits. He had been the first of forty chiefs to sign the treaty. Now would he have a brick house, na-pi-ki-sa-ming and much land to call his own. Perhaps he could even have a wagon like Pokagon’s! One thing there was that worried him. They ate no salt because they thought it brought mosquitoes. Now they would use it. Should they move farther from the water? Thus did Papakeecha reason, trying to convince himself to move beyond the hills, the pa-kwa-ki-wi, where Tipton said he should.

He was troubled, too, because his brother had no reservation. He was to have a house but where should it be built? Wawaesse claimed some land around a tiny lake alive with fish. They called it Wabees lake and by that name he was known there-after. Pakalaki bad been wooed and won by Wau-ke-wa, the’ son of Checose. They had gone to Bone Prairie to build their wickiup. Toposh, Her younger brother, helped his father make a new camp there. Trees had been all red and green and yellow; orange pumpkins and bright ears of corn were heaped in front of lodges; how they loathed to leave old Mayotika!

Came the following summer and the o-si-ma let the contract for the napikisaming for Papakeecha to James Winters of Kekionga, now Ft. Wayne. Not one word was said about the home for Wabees family, Papakeecha agreed to pay for extra cupboards which his squaw had always wanted. He alone of all me lakes chieis was to bask in white man’s luxury! Francis Minez was given a license to bring his wares and trade with them; now they could have supplies without going to Bourett’s trading post near Goshen. Land was cleared for ploughing; cattle, horses, hogs would be furnished to them later. He even planned with Metea for Kymotee to enter the Choctaw school.

But Kymotee had some other plans. He had gone with Papakeecha to the treaty grounds the fall before. He had lingered long among his fathers people. Then it was that Kymotee saw Ga-neh-yaw, Falling Snow, the niece of Me-shin-go-me-si-a. All the winter he thought about those black eyes laughing, flashing from a face he loved to look upon. Matchegan was highly pleased the youth had made his choice among his people. When frogs were calling in the marshes and the blackbirds were building nests, Kymotee journeyed southward to claim this coppery maiden.

Somewhat removed from other tribesmen, they chose a spot and built upon it. The oval frame was made of limber saplings bound together cage like with many withes of basswood. The roof was covered with squares of bark. Rush mats woven tightly were tied around the sides. A square pen was built of stones beneath, the smoke hole for the fire; a platform of smoothed poles ran all around the wickiup—here they worked or slept. Later on they hoped to have a platform outside with bark awnings.

Kymotee and his bride liked to spend much time on Mayotika. They looked for Ko-ka, the frog, At-che-pong, the turtle, Wa-pa-sa, the mussel shells and occasionally Sa-ki-wa, the craw fish. On summer nights when the pearly disc of the new moon hung in the eastern sky they liked to fish, ki-kon-as-sa, slowly gliding over the tremulous surface of the water silently lifting, dipping silvery paddles, trolling for the bass, Ci-ka-na-ki. The plaintive call of whippoorwills and On-za-wi-a-ki, the northern lights lent an air of romance to the scene.

Matchegan told them when to plan Nay-lo-min, the wild rice harvest. He prayed for the Thunder Bird to stay among the clouds. Sometimes before the Harvest Moon they tied the wild rice into bunches and later threshed them to the rhythm of the never ending lapping of the waves. More often Kymotee paddled slowly while Ganehyaw, stick in hand, bent the rice in front of her, struck the heads until the grain filled the bottom of the canoe. They never stopped until mosquitoes and the twilight of the drowsy summer forced them to leave the marsh.

Sad Years For Papakeecha.

The years which promised to be hopeful were really very sad for Papakeecha. The stock agreed upon was slow in coming. Many trips it took to Richardville to insist on all his rights. The latter had the plowing, done both for Papakeecha and White Raccoon, but the money for the live stock had been delayed two years. The tribesmen took to raiding; they were in angry mood. For half a moon Black Hawk came amongst them, tarried in their lodges, called the young men all about him. This served as a warning; the stock was sent at once and they stayed out of war.

Meanwhile white men were coming: they had damned the Turkey Creek while waiting to grab the land. The old and restless spirit came again; Wabee and Papakeecha started roving far and wide. To Me-nom-i-nee’s minotani in the Kan-ka-kee they often went or to the Deaf Man’s town upon the Mississinewa where they liked to tell of fishing through the ice or how they hunted deer at night with lights. Returning once, Wabee learned his squaw was bitten by a snake and had died the night before. Toposh, his son, had gone to Michigan where game was more abundant.

There came a summons in 1834. For the last time the brothers went away together; for the last time they met with their tribal chief. Going first to We-pe-chah-ki-ong, the “place of flints”, they continued to the treaty grounds. Here at the forks of the Wabash they were asked to yield all claim to Indiana. Here Papakeecha was persuaded to sign away his reservation which he had thought was his forever. He was sick and disillusioned: he did not feel like voicing bitter opposition which fairly seethed inside of him.

Still a further disappointment waited for him. When he approached the minotani he could not see his home. Matchegan came towards him, followed by Kymotee. They told him how Schwa-pi-na-mi, a tornado, had come across the pahwakiwi; had blown away his council house and lodge. Agounons had been injured by the falling bricks, put together all too loosely by James Winters. Matchegan had buried her. From that day on Papakeecha did not care to live. Small black eyes of a boy papoose peeping from his wooden cradle, hanging from a boug of trees nearby or on the platform of Kymotee’s wickiup was the one bright spot of Papakeecha’s life. He died a broken hearted chief.

The role of leader was assumed by Ma-cose, twin son of Musquabuck, the rover The Miamis resented this but accepted him as sullenly as they had their other circumstances. Macose had bad habits; he liked the squatters whiskey. Once, when he was “squiby”, he took a notion to cross the lake to shoot some birds, the wa – san-za-ki While coming back, and still in that condition, he “took another notion”, this time t dance upon the water. Out he went and down he went. Macose had never learned to swim.

Matchegan was called upon, after the manner of the whites, to pay a tribute to the dead man. They made mound and upon it built a rack. Macose they placed in sitting position and beside him laid his gun and implements of war.. Matchegan explained that strong drink is bad, mo-nau-dud-maish-ko wau-gu-mig” and warned his auditors of its ill effects and addressed the spirit of the bad, “mo-nau-dud-maish-ko-, drink no more on its way to the spirit land else it might stay forever in the water. The tribesmen left Macose above the ground, according to their burial custom.

Kymotee Elected Chief.

Kymotee was elected chief as he should have been before had not the interloper come. He signed one treaty and then his rule was shortened by some very sad events. Ash-cum, son of a powerful subchief, was jealous of Kymotee because he had been the successful suitor for Ganehy-aw-‘ law. Fire water, too, he drank too often. This together with his brooding caused him to kill Ganehyaw, leaving little Muk-kose without a mother. To avenge her death Kymotee shot young Ashcum. The latter had a brother. Nagget, who, roused to vengeance, in turn slew the brave Kymotee. He was forthwith put to death by one of a band of enraged Miamis. “Meanet Nagget, an-gi-hi-an-i”, meaning “very bad Nagget, me kill”, he shouted. Nagget raised his hands above his head and waited for the fatal shot. It came and he fell dead upon the sod. Thus ended the chain of tragedies which fell upon our Indians of the lakes.

But there was still a further blow, a final one it proved to be. The sun was setting; game was disappearing; hunger stalked amongst the tribesmen. While they met to celebrate a festival upon the |lake shore, the men danced as Matchegan directed while all the squaws looked on. They were interrupted with cries from all the women: they were pointing to a red sky in the southeast. Heartless squatters had applied the torches in their absence; all the wickiups were burned, Nothing was left of the mi-notani but scattered bricks which white men later found, and carried away for chimneys.

The councils fires could blaze no more: the camp fires were extinguished. It was a sad and mournful spectacle when children of the forest, led by their bent and wiry medicine man holding the hard of dead Kymotee’s son, Muk-kose, the Little Beaver, slowly left their hunting grounds, their sturdy battlefields the wilderness which held the graves of revered ancestors. Sad and broken hearted, all hope vanished. They cast upward glances imploring the, Great Spirit to redress their wrongs. A few glass beads; an arrow head, some mustv records and tradition—that is all there is left to tell the story of the Indians of our Lakes. “Whither they went and how they fared Nobody knew and nobody cared”. – Barce